After Detention: Exhibition on Asylum Seekers in Japan (10/25)

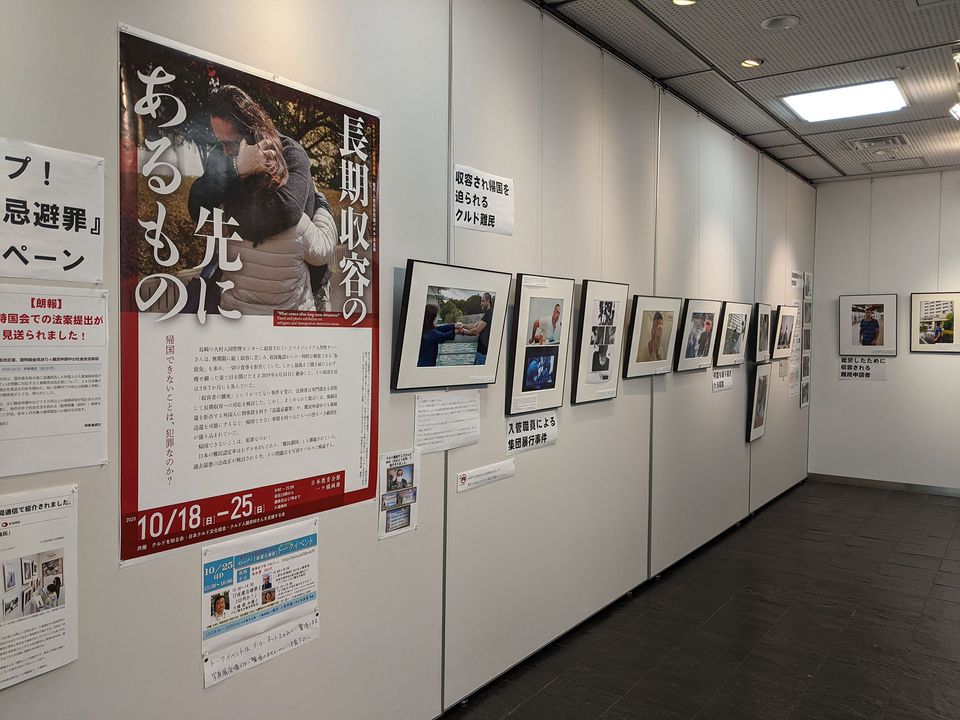

For one week from 10/18 to 10/25, photojournalist Sachiko Saito and the Society for Understanding Kurds hosted an exhibition in the Japan Education Center exploring the persecution that Kurdish refugees and other asylum seekers face through Japan's broken and racist immigration infrastructure.

本日より25日まで、短い間ですが神保町の一ツ橋会館で写真を展示してます。「送還忌避罪」というヤバい刑事罰が作られそうになっていて、それによって「罪人」にされてしまうのは、私たちの友人かもしれないという事を伝えようとしています。お近くに寄る際はぜひ見に来てください。 pic.twitter.com/YOM72M1LpS

— 齊藤幸子 Sachiko Saito (@sachikomsms) October 18, 2020

Last month, the U.N. Working Group on Arbitrary Detention published an opinion brief calling Japan's long-term detention of immigrants and asylum seekers arbitrary, and thus a violation of international human rights law. The brief detailed the experiences of Deniz and Heydar, who have been detained on and off months at a time for over a decade at Higashi-Nihon Immigration Center in Ushiku, where they and other detainees have suffered wanton violence from detention officers while refused adequate medical care. As the exhibition highlighted through its profiles of other immigrants, however, provisional release from the detention center is but an extension of detainment, for as long as one is denied residency status, they are unable to work or even leave their designated district. Apparently, the Japanese government would sooner cut off any possibility of maintaining a livelihood here before providing an immigrant or refugee their visa.

Despite these human rights violations, a committee under the Ministry of Justice has proposed criminalizing immigrants who refuse repatriation in order to coerce them into leaving themselves, ignoring the circumstances – from family and children in Japan to the threat of violence in their home country – that would lead an individual to choose staying in the first place. Somehow the proposal comes as a response to Nigerian detainee Sunny's death from starvation in a hunger strike protesting his prolonged detention in Nagasaki. According to the committee, the reason for Sunny's death was that "repatriation could not be carried out," and that their aim was to make those who would otherwise refuse repatriation consent.

In response to a survey asking each political party's position on criminalizing those who refuse repatriation, the Japanese Communist Party, the Social Democratic Party, and the Democratic Party for the People have emphasized the need for reform that protects the rights of foreigners in Japan, although as of writing only the Communist Party has firmly stated its opposition. Other parties, including the incumbent Liberal Democratic Party, are either unclear in their opinion or have yet to respond, which in the face of such clear disregard for humanity is both revealing and disappointing.

The exhibition displayed coverage of Kurdish immigrants' battles with Japanese immigration policy from over the decades. In addition to Deniz's lawsuit this year against the Japanese government to claim damages for the violence he suffered in detention, I also learned about Amhet Kazankiran and his son Ramazan, who were deported in 2005 despite being recognized by the UNHCR as "mandate refugees," and Erdal Dogan and his family, who were granted asylum in Canada a few years later despite struggling to gain refugee status in Japan.

The Kazankirans and Dogans had arrived in Japan in 1990s, and for years sought asylum due to fears of persecution back home, only to be constantly turned down and merely granted provisional release from detention. In 2004, the two families staged a a 72-day sit-in in front of Tokyo's United Nations University demanding justice, but were ultimately ignored by the Japanese government. After the Kazankirans were deported, Erdal Dogan applied for refugee status in Canada instead, and succeeded in his bid just two years later. Despite his victory, Dogan expressed frustration, too. "I spent eight and a half years – that is one fourth of my life – in Japan, learning the language and culture, and I wanted to stay here," he explained to The Japan Times. "Now, my family will have to start all over again."

As Saito writes in the introduction to her photo series featuring Kurdish teenagers living in Kawaguchi, Saitama, even kids growing up and going to school in Japan bear a similar burden of an uncertain future. Whether they will be able to stay is left up to the arbitrary decision-making of an ineffectual system. Nevertheless, she adds, they are living their youth. Each portrait included a handwritten note written by the subject – one girl wrote that her dream was to become a hairdresser, another explained that she was planning on applying to college next year.

As I learn more about the struggles that other foreigners in this country face, I reflect on how easily the intersections of racial and economic privilege inhibit our solidarity as an international community. The classist, racist euphemisms of visa denominations serve to keep us separated, and allow the most privileged the greatest platforms for sharing their insulated experiences, while far more common hardships are rendered outliers, i.e, the fault of a single burakku kigyo or industry, and not the consequence of a fundamentally flawed infrastructure that perpetuates harm against the poor and Brown.

The truth is that we all live here precariously, and that at best, all that stands between ourselves and the whims of unchecked authorities is a date. Thus, for us to treat the plight of any community or people under government-regulated activity as beyond our concern is not only tantamount to an endorsement of structural violence, but also a reckless leap of faith, as we could have been, and could always be, just another target.

とりあえず最悪オブ最悪な事態にはならないようで安心しましたが、まだまだ最悪なままです。神保町での展示25日までですのでよろしくお願いします。

— 齊藤幸子 Sachiko Saito (@sachikomsms) October 22, 2020

Let kids be kids!! https://t.co/bq5Tffsfgo pic.twitter.com/qELsxwFNgH